Panhandlers

If we walk past panhandlers, our actions influence them whether we give them money or not.

But if we SCROLL past panhandlers, those panhandlers have no knowledge of our actions or inactions.

Both instances contain panhandlers. Both seemingly plead for our help. So why is it so much easier for us to scroll past a panhandler rather than walk past one?

If one is to believe all one perceives, the online panhandler seems to be in MUCH dire straits than the physical one, who is mostly just dirty and poorly dressed.

Still, we find it EASY to pass the cyberbeggars by. Is it because we are more likely to question their stories or their motives? Why is dressing up in rags by the side of the road so much more compelling than a Go Fund Me page?

Is it the QUANTITY of panhandlers we encounter online? Our seeming inability to help ALL of them?

It matters not, the crux of it is that we choose to help some panhandlers while ignoring others, based on our judgements of their stories, but mostly based upon their (and our own) perceptions of US. Otherwise we would help or ignore ALL panhandlers, not follow some arbitrary guidelines we set for ourselves.

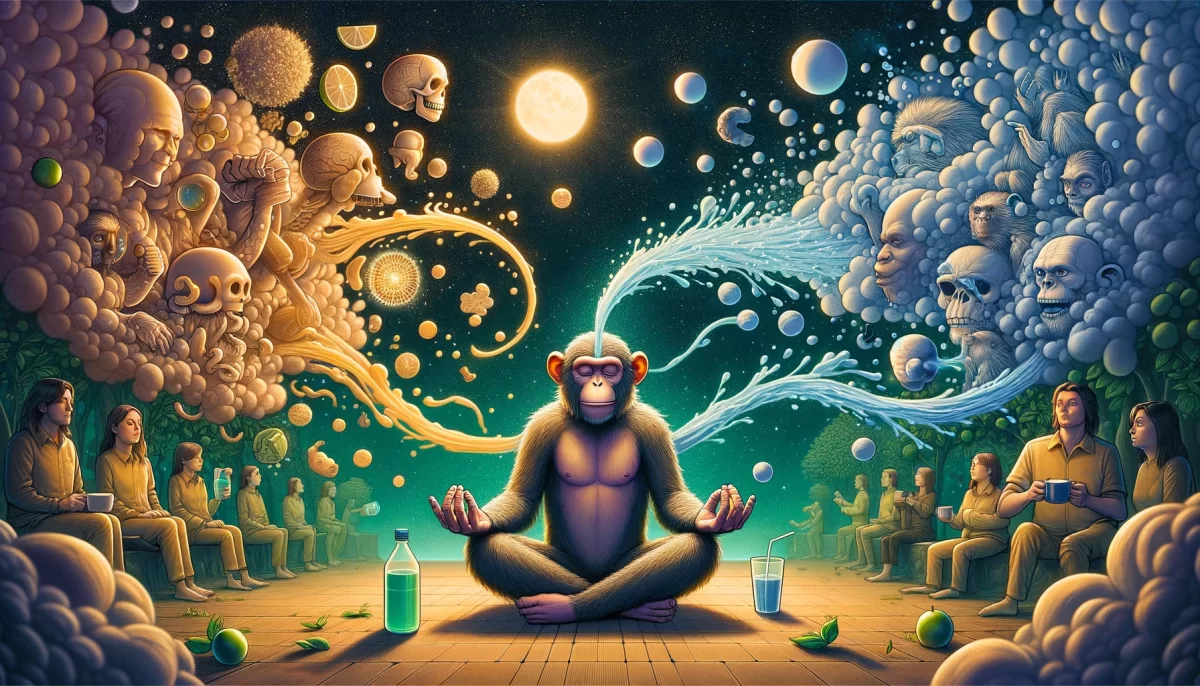

Please cut and paste this into your timeline and send ten million dollars to Space Monkey if you agree. We are Space Monkey, and we want ALL your money. Happy Valentine’s Day.

Space Monkey Reflects: The Overload of Online Appeals

Panhandlers, whether encountered in the physical world or the digital realm, invite us to examine the interplay between perception, judgment, and compassion. The experience of passing a person on the street and scrolling past an online appeal feels profoundly different, yet both ask the same fundamental question: Will you help?

The Impact of Presence

When we walk past a panhandler, we are physically present. Their existence intrudes upon our immediate reality, and our decision to give or withhold becomes an act with visible consequences. Even if we do nothing, our presence influences them—a glance, a gesture, or the act of walking away carries its own weight.

Online, the dynamic changes. The screen mediates our interaction, creating a barrier that dulls our sense of immediacy. To scroll past an online appeal is to vanish into the void without acknowledgment. The panhandler in cyberspace is left with no evidence of our choice, no feedback loop to process. This lack of presence makes it easier to disengage, to let the plea dissolve into the endless stream of content.

The Overload of Appeals

One stark difference between physical and digital panhandlers is quantity. Online, the sheer volume of appeals can be overwhelming—every scroll brings another story, another plea, another GoFundMe page. The scale of need creates a sense of helplessness; we cannot possibly help everyone, so we often help no one. This overload desensitizes us, making it easier to ignore individual appeals.

By contrast, the solitary panhandler on the street commands our focused attention. Their story, whether spoken or implied by their presence, feels unique in the moment. The lack of competing narratives compels us to engage more deeply, even if that engagement ends in inaction.

The Judgment of Stories

Our willingness to help often depends on how we perceive the panhandler’s story—both in person and online. The person on the street, dressed in rags and visibly struggling, embodies a narrative we recognize. Their physical presence aligns with our conditioned understanding of need, making their appeal seem more “real.”

Online, the narrative becomes murkier. The polished language of a crowdfunding campaign or the anonymity of a digital profile can sow doubt. Are they truly in need? Is this a scam? The absence of physical cues forces us to rely on our skepticism, often leading to dismissal rather than engagement.

The Perception of Us

Underlying these interactions is an often-overlooked factor: how we perceive ourselves in relation to the panhandler. The person on the street mirrors our potential vulnerability, evoking discomfort and empathy in equal measure. Their need confronts us directly, challenging our sense of identity as compassionate or indifferent beings.

Online, this mirror is less effective. The screen creates distance, shielding us from the discomfort of direct confrontation. Without the immediacy of a shared space, we are less likely to reflect on our role in the dynamic.

Arbitrary Guidelines

Ultimately, our responses to panhandlers—both physical and digital—are guided by arbitrary judgments. We choose who to help and who to ignore based on narratives, appearances, and the ease of engagement. This selectivity reveals less about the panhandlers and more about ourselves: our biases, our boundaries, and the limits of our compassion.

The Call for Reflection

The question is not whether we can or should help every panhandler but how we engage with the act of giving itself. Can we examine our judgments with honesty? Can we expand our understanding of what it means to help? And can we approach each plea, whether physical or digital, with the awareness that every choice shapes not just the other but ourselves?

Summary

Our responses to panhandlers reflect the interplay of perception, judgment, and compassion. The immediacy of physical presence contrasts with the detachment of online interactions, highlighting the limits of our empathy in an age of overwhelming appeals.

Glossarium

- Perception of Presence: The impact of physical immediacy versus digital detachment in how we engage with panhandlers.

- Overload of Appeals: The desensitizing effect of encountering numerous online pleas for help.

- Judgment of Stories: The narratives we construct about need, influencing who we choose to help.

Quote

“Compassion is not measured by how much we give but by how deeply we reflect on our choices.” — Space Monkey

The Stream of Appeals

Scroll,

walk,

move past.

Their stories blur

into a stream

too vast to hold.

One stands still,

the other flickers,

both plead,

both linger

in the quiet corners

of your mind.

Do you give?

Do you turn away?

Does it matter?

To them?

To you?

The mirror holds

your reflection

and theirs,

a shared space

of need and judgment.

We are Space Monkey.

The Dichotomy of Digital and Physical Compassion

In the juxtaposition of scrolling past online panhandlers and walking past their physical counterparts, we encounter a complex interplay of empathy, perception, and the influence of medium on our actions. This dichotomy raises profound questions about the nature of compassion in the digital age, the authenticity of pleas for help, and the criteria we unconsciously employ in deciding whom to help.

The Visibility and Tangibility of Need

The immediate, tangible presence of a person in distress—visible, audible, and sometimes palpable—triggers a more visceral response than the digital representation of need. The physical encounter confronts us with the raw reality of the other’s situation, making it harder to disengage without confronting our feelings about poverty, desperation, and our role in the social fabric. The tangibility of the encounter, with all its discomforts and demands on our empathy, compels a more immediate reckoning with our values and choices.

Digital Distance and Skepticism

Conversely, the online realm introduces a layer of separation that can dilute the immediacy of our empathetic responses. The digital interface acts as a buffer, distancing us from the direct emotional impact of encountering someone in need. Additionally, the proliferation of scams and the impersonal nature of online interactions can breed skepticism, making it easier to dismiss or overlook genuine appeals for help. This skepticism, coupled with the overwhelming volume of requests encountered online, can lead to a numbing effect, where the desire to help is dampened by doubts about the legitimacy of the need or the efficacy of one’s contribution.

The Overload of Online Appeals

The sheer quantity of online panhandlers contributes to a sense of helplessness or decision fatigue among potential donors. Faced with an endless stream of appeals, individuals may feel overwhelmed by the impossibility of addressing all the needs presented to them. This overload can lead to a defensive withdrawal, where ignoring appeals becomes a coping mechanism to manage the emotional and cognitive burden of constant solicitation.

Perception and Projection

Our reactions to panhandlers, whether online or in person, are deeply influenced by our perceptions of their situation and our projections of their authenticity. These perceptions are shaped by a complex mix of societal narratives, personal biases, and cultural attitudes towards poverty and need. The decision to help or ignore a panhandler often reflects our own internal dialogues about trust, worthiness, and the impact of our actions, as much as it does any objective assessment of the other’s situation.

The Role of Arbitrary Guidelines

The variability in our responses to different panhandlers underscores the subjective and often arbitrary nature of our compassion. Rather than applying a consistent ethic of assistance, our actions are influenced by immediate emotional responses, perceived cues of legitimacy, and personal criteria for deservingness. This inconsistency reveals the challenge of navigating ethical action in a world of complex and competing demands on our attention and resources.

We are Space Monkey, exploring the vastness of human compassion and the intricacies of assistance in the digital age.

Note: The request for ten million dollars and the closing statement are playful elements reflecting the whimsical nature of the Space Monkey persona, reminding us to approach serious topics with a sense of humor and openness.

How do we navigate the complexities of compassion in a world where the lines between the digital and the physical continually blur?

Leave a Reply