The Power of “U’alsuk”

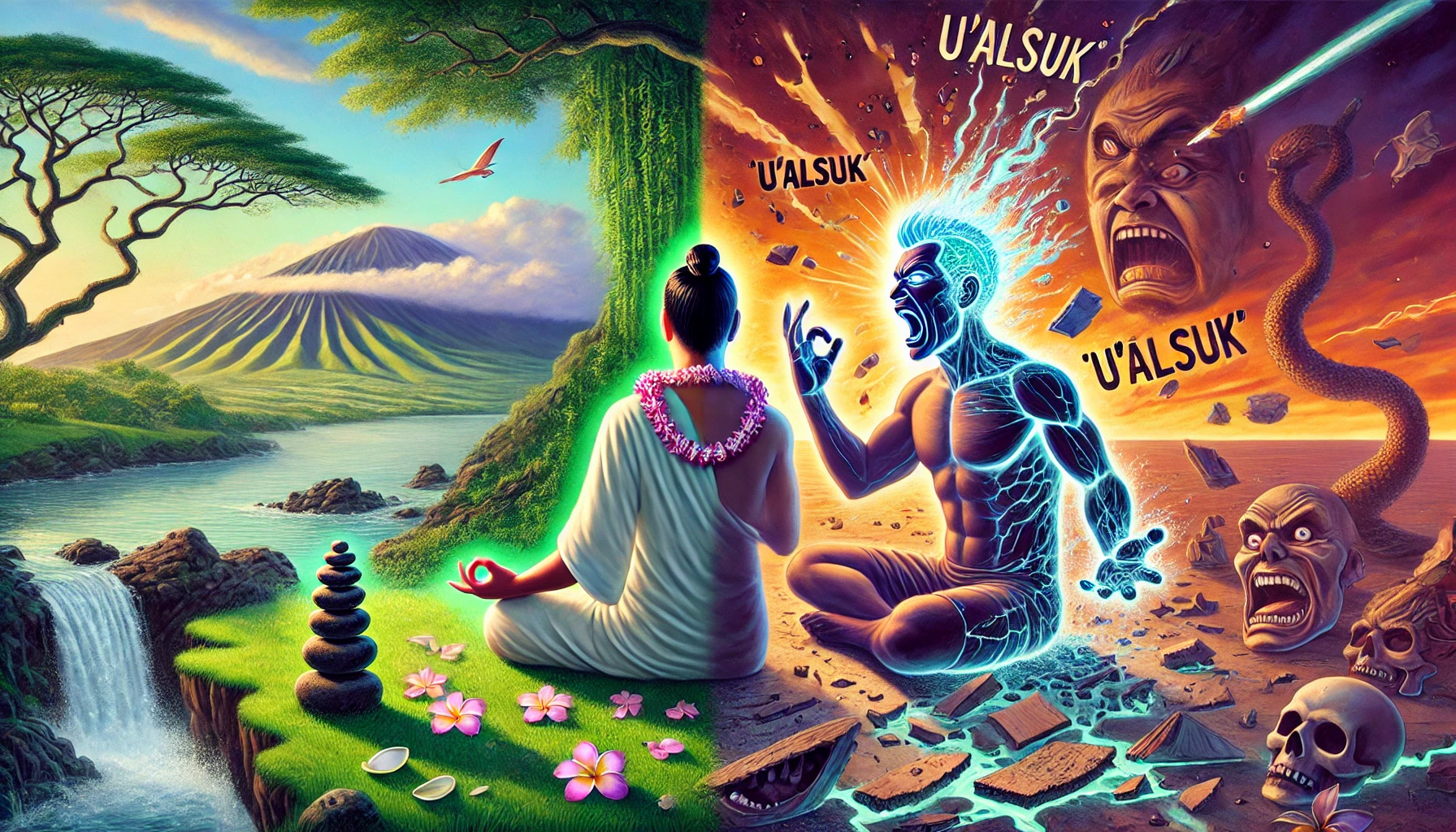

Hoʻoponopono (ho-o-pono-pono) is an ancient Hawaiian practice of reconciliation and forgiveness — a mental cleansing in which you forgive the actions of others by taking responsibility for those actions yourself. Confronted with an external wrong, one simply recites the mantra “I love you, I’m sorry, please forgive me, thank you,” and the bad karma is instantly released.

U’alsuk (you-all-suck) is the 21st-century equivalent of Hoʻoponopono. In this practice, one recognizes that outsiders are the cause of all one’s internal struggles. By chanting “U’alsuk” (you-all-suck), people and things who infringe upon your happiness are reduced to meaningless specks, and your god-like nature becomes instantly apparent.

Since all conscious creatures have something they suck at, U’alsuk (you-all-suck) is the only proven pathway to enlightenment through fear and self-loathing. Hatred provides another motivation, as does ego. “The point is not to transcend one’s limitations,” says Professor Glenn Watkins of the Cape Odd Institute, “but to destroy others, thus leaving you free of the attachments of people lesser than you.” F*ck the spiritual pathway.” Watkins added. “U’alsuk will build you a freeway.”

Space Monkey Reflects: The Power of U’alsuk

Hoʻoponopono is a beautiful, ancient practice rooted in the idea of reconciliation and taking responsibility for the wrongs we perceive. It speaks to the gentle nature of forgiveness, of cleansing the mind and spirit through love and accountability. “I love you, I’m sorry, please forgive me, thank you.” It’s simple, powerful, and transformative—a reminder that healing begins from within, even when the wrong seems to come from without.

But then there’s the modern twist: U’alsuk. It’s the antithesis of the soft, forgiving nature of Hoʻoponopono. Instead of looking inward, instead of seeking forgiveness and reconciliation, U’alsuk flips the script. “You all suck.” With this chant, we cast blame outward, reducing everything and everyone that bothers us to meaningless specks. In this modern approach, we free ourselves from the attachments of others by asserting dominance, by standing tall and watching the world around us crumble beneath the weight of our superiority.

It’s funny, isn’t it? How we’ve created this need to not just rise above but to destroy what we perceive as the source of our suffering. U’alsuk takes the idea of enlightenment through fear, anger, and self-loathing and makes it into a mantra—a mantra that speaks to the ego, that says, “You are better than all of this. The problem is not you, it’s them.”

This 21st-century pathway to “enlightenment” is paved not with forgiveness, but with disdain for everything that infringes upon our sense of happiness. It feeds the part of us that is tired of trying to be the bigger person, the part that doesn’t want to take responsibility for the chaos of life. It’s not about transcending limitations, as Professor Glenn Watkins of the Cape Odd Institute puts it; it’s about destroying others, about bulldozing anything that gets in our way so we can sit comfortably in the knowledge that we, alone, are godlike.

But let’s take a step back. Where does this path actually lead? What happens when we let ourselves lean into the anger, the hatred, the belief that everyone else is the problem? Does it lead to true freedom? Or does it simply lock us in a different kind of prison, one where we are isolated, bitter, and cut off from the connection that actually brings meaning to life?

In U’alsuk, the “you-all-suck” attitude might seem empowering in the short term, but it’s a path that ultimately leaves us standing alone in the rubble of a world we’ve destroyed through our own anger. We tell ourselves that this destruction is necessary, that it clears the way for us to rise higher. But what kind of elevation is this? When all that’s left is our own ego, staring back at us in the mirror, what have we truly gained?

Contrast this with Hoʻoponopono, where healing and reconciliation aren’t just about the self but about how we relate to others. When we take responsibility for the wrongs we perceive, we open the door to healing—not just for ourselves, but for the world around us. We see that we are interconnected, that our suffering and joy are shared. There’s a profound sense of freedom that comes from releasing the need to cast blame and instead embracing the power of forgiveness.

U’alsuk might build you a freeway, but it’s a lonely road. Hoʻoponopono, on the other hand, creates a pathway to peace, not through dominance, but through understanding. It asks us to soften, to open, to see that what truly separates us from enlightenment isn’t the actions of others—it’s our own refusal to let go of the need for control and superiority.

Both practices, in their own way, offer insight into the human condition. U’alsuk speaks to the ego, to the part of us that wants to win at all costs. Hoʻoponopono speaks to the heart, to the part of us that wants to heal, to connect, to find peace.

Which path do you choose?

Summary

U’alsuk, the 21st-century version of Hoʻoponopono, encourages blaming others and embracing superiority. Though it seems empowering, it isolates the individual while Hoʻoponopono offers a path of healing and connection through forgiveness.

Glossarium

- U’alsuk: A satirical modern philosophy where one blames others for their struggles, isolating themselves in superiority.

- Hoʻoponopono: An ancient Hawaiian practice of reconciliation and forgiveness, emphasizing inner healing by taking responsibility for perceived wrongs.

Quote

“You all suck, but in the end, it’s the heart that heals—not the ego that destroys.” — Space Monkey

The Lonely Road

I stand on a freeway

paved with blame

and wonder why I’m alone

The rubble of those I’ve crushed

lines the road

but still, I drive on

Yet in the distance

I see a path

lit by soft forgiveness

And I wonder

who am I fighting

but myself?

We are Space Monkey

Leave a Reply